The Filipino President Just Set Off a Diplomatic Earthquake

Rodrigo Duterte’s tilt toward China is a fundamental shift in the Western Pacific power balance.

t is one thing for a leader such as Vladimir Putin to send all of Washington and the media clerks serving it into a dither—as the Russian president has on numerous occasions. Favor or detest him, Putin is an exceptional statesman by any disinterested measure. It is quite another matter for the leader of a small, poor, traditionally meek client such as the Philippines to tie our policy cliques in knots, as that nation’s 16th president has just done.

Rodrigo Duterte—“Digong,” in a nation that gives everyone a nickname—is far from accomplished as a statesman; next to Putin, it must be said, he can come across to some as a blunt instrument. In a shorthand I find useless, Duterte is known on our shores as a right-wing populist out of the Donald Trump file. This is reductionist, obscuring far more than it reveals—which may be precisely the point: The last thing our policy cliques and pundits want to do is understand and face what Duterte is driving at (and what drives him).

Since he was elected in May by a considerable margin, Duterte has drawn attention primarily for a campaign against drug peddlers and addicts that he wages by way of the police and vigilante death squads in the Latin American mode. So far, Duterte’s drug war has claimed more than 3,000 victims, half or more of them extrajudicial murders. It is a dreadful mess, as the United Nations and many human-rights organizations have vigorously asserted. But Filipino voters knew this was coming when they sent Duterte to Malacañang Palace: In the 20–odd years he served as mayor of Davao, a large city in the south of the archipelago, a similar war against the Philippines’ vast and tragic drug culture claimed roughly 1,500 lives.

As of last week, being appalled by Duterte’s law-and-order tactics has given way to being appalled by his foreign policy—a rather larger matter. Since assuming office he has made no secret of his contempt for the “little brown brother” tradition of sycophancy he inherited from all previous residents of Malacañang. For some time, this amounted to a pile of epithets Duterte sent the White House’s way. He has called President Obama “the son of a whore” on repeated occasions. “Mr. Obama, you can go to hell,” he said in a speech delivered in Tagalog earlier this month. In a matter of substance, Duterte swiftly signaled that he would reject a Hague tribunal’s ruling in July in support of Manila in its dispute with China over maritime claims in the South China Sea. But Washington did not make much of Duterte’s position. This was to my surprise, given that it was Hillary Clinton’s State Department that railroaded Benigno Aquino III, Duterte’s predecessor, onto the legal track. (Manila filed its suit in The Hague a matter of days after Clinton stepped aside as secretary of state in 2013.)

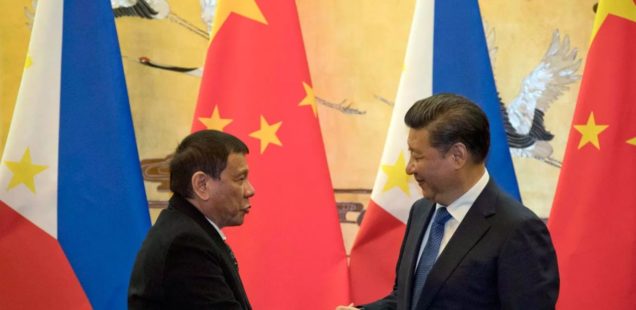

That now looks like an immense, collective flinch, for Duterte’s summit with Xi Jinping in Beijing last week confirms what the State Department and the White House ought to have seen coming but missed by many miles. Here are a few of Duterte’s remarks prior to meeting the Chinese president. He addressed his remarks to the United States before an audience of Filipino expatriates:

“You stay in my country for your own benefit. So it’s time to say goodbye, my friend.”

“I will not go to America anymore. I will just be insulted there.”

“No more American interference. No more American [military] exercises. What for?”

“What kept us from China was not of our own making. I will chart a new course.”

The last of these assertions is especially interesting. It amounts to official confirmation that Washington was the prime mover behind the Hague lawsuit from the start—Manila going along with the same reluctance it often harbors but conceals in its relations with the United States.

The morning after Duterte’s stunning speech, he and Xi signed 13 trade and investment agreements worth $13.5 billion; billions more in soft loans are in the discussion phase. China will lift trade and travel restrictions it imposed when the South China Sea dispute got hot four years ago. The two sides are now formally committed to negotiating a settlement of maritime claims, in all likelihood awarding Filipino fishing boats access to Scarborough Shoal, where tensions have been most acute. “There are three of us against the world: China, the Philippines, and Russia,” Duterte said, this time in the Great Hall of the People. “It’s the only way.”

It is possible that Duterte is posturing for the sake of advantage in the US-Filipino relationship, which is in essence neocolonial. But I doubt it at this point, for reasons I will explain. This is more than a diplomatic earthquake. It augurs a fundamental shift in the power balance in the western Pacific. Yasuhiro Nakasone, Japan’s premier during the Reagan years, once called his country “a floating aircraft carrier” for all the American naval and air facilities it hosts. The Philippines has been another such strategic asset since Teddy Roosevelt dreamed imperial dreams in the early 1900s. And now, as Duterte made explicitly clear this week during a state visit to Japan, he wants to “revise or abrogate” a recent agreement that allows the United States to lease Filipino military bases, after more than a century of privileges only interrupted in the 1990s.

Pretty big doings for a down-home provincial pol with a lot of moxie, not much polish, and no experience whatsoever in an international context. What are we to make of Rodrigo Duterte? Filipinos, let us not forget, give their new president notably high approval ratings—notwithstanding the murder count in his drug war and their famous affinity for American people (if not American policies). What is the draw in the message Duterte articulates so pugnaciously?

* * *

Forget about the Duterte–Donald Trump analogy. The comparison from which we can learn something is with Sukarno, Indonesia’s larger-than-life president from the nation’s 1945 independence until a CIA-supported coup deposed him in 1967. The great Bung, students of history will recall, gave the developing world a superbly inspiring display of defiance in late 1964, by which time he knew Washington had it in for him, as it did for all nonaligned leaders. “Go to hell with your foreign aid!” Sukarno declaimed in one of those grand speeches he favored. Talk about speaking truth to power. I have always wished I understood Bahasa so I could listen to some crackly recording of so memorable a moment.

It is unlikely Duterte makes a study of Sukarno’s rhetoric, but never mind: There is a straight line from the Indonesian leader’s “go to hell” and the Filipino’s. They are both lifters of the lid on two things we Americans are not supposed to grasp. One, the nations of Southeast Asia were Washington’s Cold War satellites, nothing more, just as those of Eastern Europe were Moscow’s. The only differences lie in style and America’s preference for bribing local populations materially to induce cultures of political quietude. Two, neocolonialism is not fun if you are on the receiving end of it. Duterte is one with Sukarno in drawing this conclusion.

This is why one must take the Filipino president’s démarche to Beijing seriously. It arises from a long and deep ressentiment abroad among Asians—unmistakable once one connects with it, invisible until then. For my money, historical realities suggest the Philippines will end up—irony of ironies—as none other than nonaligned between the United States and those nations Washington systematically shapes into its current crop of enemies. And if there is one lesson Duterte should indeed take from the Bung, he will do well to keep Malacañang’s security detail spit-shine disciplined. Leaders who have done far less have gone Sukarno’s way.

Duterte’s campaign against drugs and the illicit industry that puts them on the Philippines’ streets cannot be condoned, but neither can it be judged separately from the above-noted considerations. Nor can aspects of his personal history, notably his opposition to the Vietnam War when young, the corruption and repression of the Marcos years, and his reverence for José María Sison, a former teacher long in exile for his leftist activism. What does Duterte’s determination to wipe out a debilitating drug culture reflect, if not aspiration well mixed with shame that the nation he leads—the “pearl of the Orient” in the immediate postwar years—has been brought so low after 60-odd years of “tutelage” (or whatever one wants to call it) at the hands of Americans? What is he if not a conscientious objector who has breathed the air of neocolonialism the whole of his 71 years?

In the days since Duterte’s summit with Xi, Washington has done what it always does whenever events contradict its presumption of eternal primacy. It is “studying” Duterte’s remarks. John Kirby, the dullard who fronts for State these days, had the honesty to acknowledge last week that the administration is “baffled.” Invocations of a long friendship between Filipinos and Americans are deployed to airbrush out the betrayal of Jefferson-reading Filipino democrats in the last years of the 19th century and the savagery of the war that followed. Having promised arms and assistance to Emilio Aguinaldo, the anti-Spanish uprising’s leader, the Americans betrayed his movement as soon as the Spanish were out of the way. It was in the years that followed, instructive to note, that American soldiers coined that attractive term for Asians, “gooks.” No Filipino forgets this history, just as the Opium Wars were yesterday in the Chinese consciousness.

The award for nitwittery in this line has to go to Max Boot, late of the Council on Foreign Relations, now writing for Foreign Policy, and ever a courageous defender of the safely orthodox. Having wrung sweaty hands for many paragraphs, Boot concluded last Thursday, “This massive geopolitical shift is entirely Duterte’s doing. It cannot be explained any other way. It is a product of his peculiar psychology.”

Must be, Max. Nothing else to it. Back to the cubicle.

Anything, anything, anything to avoid the onrush of the 21st century—an essential feature of which, as I have often argued, is the achievement of parity between West and non-West. This is Duterte’s true topic—and Xi’s, and Putin’s, just as it was Sukarno’s and Ho’s and Zhou Enlai’s. And since the breaking news of our time now arrives in Washington in great lumps and ever more persistently, we may as well consider desperate avoidance of this kind a symptom of Washington’s condition: It is a deer caught in headlights when leaders even of small nations such as Duterte’s speak their minds.

The conclusion of Lawrence’s interview with Chas Freeman, the first part of which was published on October 14, will be posted shortly.